Middle of Everywhere

Architectures of

the Kansas Flint Hills

Curated by Timothy A. Schuler & Derek Hamm

May 4–25, 2019

The Volland Store, Volland, Kansas

Read the accompanying article published in Places Journal →

Middle of Everywhere explores the relationship between people and landscape through the prism of architecture—the hidden, the everyday, and the aspirational. By widening the aperture beyond traditional parameters, these images challenge the dominant narrative of architectural history in the Kansas Flint Hills and draw attention to histories in danger of being forgotten. Even as more contemporary work demonstrates architecture’s ability to make a rare and endangered landscape legible, its juxtaposition with the built infrastructure of colonial-capitalism is a reminder that architecture is a revealing art, a mirror that reflects humanity back to itself.

Historical Context

Back to top ↑

The Flint Hills boasts one of the strongest burn cultures in the United States. Before Euro-American settlement, the Kanza people and other indigenous groups set fire to the tallgrass prairie in order to spur new grass growth and attract wildlife, such as bison and deer. Prairie fires also occurred as a result of lightning strikes, and early settlers built limestone structures not only because of the material’s abundance but because it could withstand a conflagration. Ecologists and rangeland managers are increasingly aware of the role that fire plays in the tallgrass prairie ecosystem, and the built environment has begun to reflect fire’s omnipresence, with materials that provide fire resistance, such as steel or concrete stucco. This burn took place within Manhattan city limits.

Fire reveals the underlying architecture of the Flint Hills. The region’s limestone shelves, laced with chert, were first deposited in the Permian period, when Kansas was a shallow sea. Besides producing more nutritious growth in the region’s grass species, prairie burns prevent the encroachment of eastern red cedar and other woody species, among the most significant threats facing the Flint Hills.

A slab of limestone is processed at U.S. Stone Industries’ facility in Herington, Kansas. The Flint Hills contains some of the highest quality building stone in North America. At one time, the region exported more limestone than it did cattle. Locally, limestone was used for everything from houses to bridges to storm cellars. Although it remains in high demand for building projects across the country, limestone today is mostly used decoratively, even as its production has become increasingly mechanized.

In 1859, after much coercion, the Kanza tribe were consolidated onto 80,620 acres southeast of Council Grove. In the years following, the U.S. government constructed 138 small, limestone houses for tribe members and their families. The single-room structures measured 16 by 20 feet and sat on 40 acres that were to be used for crops or livestock. Many of the Kanzas refused to live in the houses, however, and instead used the huts as stables for their horses and dogs. Euro-American settlers later occupied some of the houses. Today, the ruins of three houses, including this one, stand within the boundary of Allegawaho Heritage Memorial Park south of Council Grove.

Far less grand than the mansions of men like Stephen Jones, the Shaft House is more typical of early homesteaders. Constructed in 1857, four years before Kansas became a state, it is the oldest existing limestone structure in Chase County. The house was built by William and Jane Shaft, who moved to Kansas territory from Michigan. A large, two-story addition was added in 1868. The house was built from stone quarried nearby in a vernacular Greek Revival style. Many early limestone structures also featured locally made mortar, made from limestone cooked in large kilns located throughout the Flint Hills.

Built in 1920 by the McNee family, this gabled-roofed horse barn was part of a large tenant farming operation south of Elmdale in the Cottonwood River Valley. The barn features a structure of limestone and timber, with a coursed limestone foundation and rubble walls finished with a parged coating. Nearby is a less common typology: a boxcar barn, constructed by placing two boxcars parallel to one another to form a bay and topping the structure with a timber-framed roof. Boxcar barns were common during economic downturns, and in the period after World War II, a wooden boxcar could be purchased for $65.

Built near the top of a rise directly adjacent to the Burlington North Santa Fe railroad, this structure is one of few remaining section houses in Kansas. Constructed every roughly eight miles miles along the line, the section hands who maintained the track lived in these company-constructed bunkhouses. Many of the laborers were Mexican immigrants, and they referred to the bunkhouses as “las casitas,” or “the little houses.” Before the section houses were built, laborers were forced to live in ad hoc structures constructed from scrap metal and railroad ties, with boxcar doors occasionally used for roofs. Although from a distance the walls of the section house appear to be limestone, the material is rock-faced concrete block, an economic alternative to quarried stone that became popular in the early 20th century and was eventually mass produced. The building was restored and converted into vacation rentals in 2006.

Contemporary Projects

Back to top ↑Hodgdon Powder Co.

El Dorado Inc., 8,500 square feet of new office and support space, Herington, KS, 2007

- East elevation

- Employee breakroom

- Changing room and showers

- Awning

- Building site

Wabaunsee County Homestead

El Dorado Inc., rehabilitation of 350-square-foot, circa 1893 limestone structure, 1,150-square-foot addition, Wabaunsee County, KS, 2016

- South elevation

- Interior, new addition

- Patio, looking southeast

- Master bedroom, historic structure

- Section diagram

Preston Outdoor Education Station

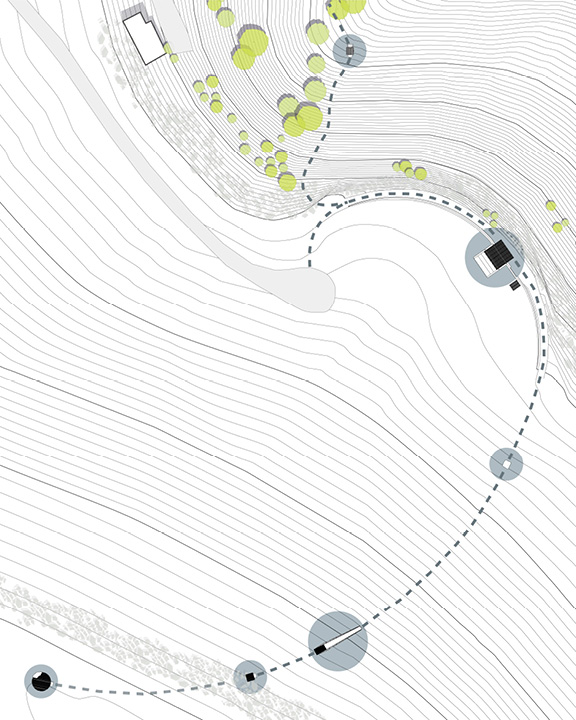

KSU Design+Make Studio (David Dowell, instructor), 1,300-foot trail system with interpretative signage, viewing platforms, Camp Wood, Elmdale, KS, 2016

- Gathering Station

- Sky Station

- Site plan

- Construction

- Charred wood detail

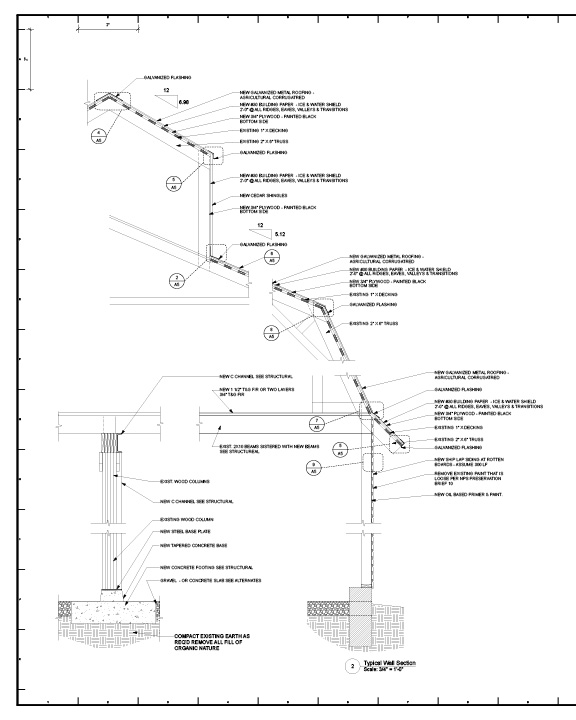

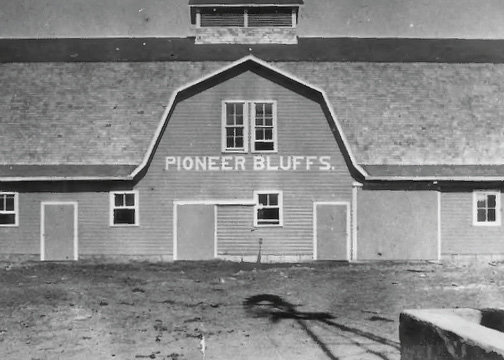

Pioneer Bluffs Barn

Ben Moore Studio, adaptive reuse of 4,900-square-foot barn (circa 1915), Matfield Green, KS, 2015

- Second floor event space

- West elevation

- First floor event space

- Wall and roof details

- Historic context

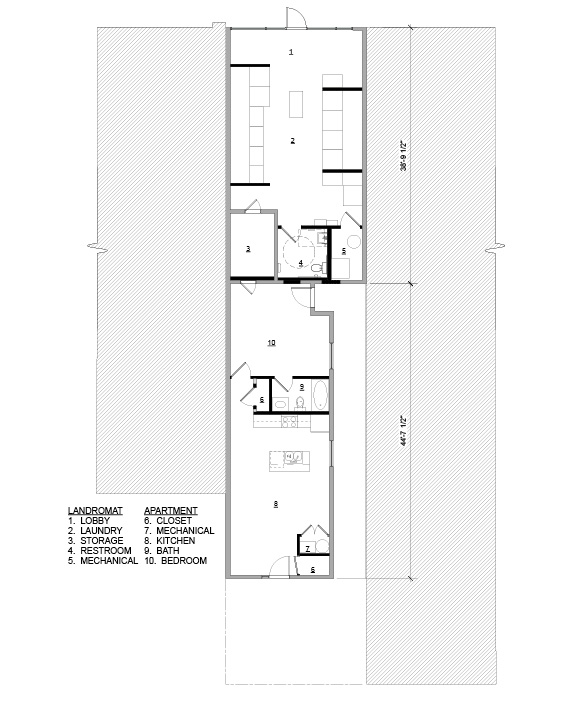

Wash-O-Rama

Ben Moore Studio, Davis Preservation, adaptive reuse of circa 1900 building for commercial laundromat and rental housing, Cottonwood Falls, KS, 2016

- Restored facade

- Interior, laundromat

- Interior, residential unit

- Floor plan

- Existing condition

Ridge Residence

Rod Harms and Stephanie Rolley, 4,500-square-foot straw-bale construction for private residence, vacation rental, and event space, Manhattan, KS, 1996

- West elevation

- North elevation

- Framing

- Application of stucco

- Concrete footing

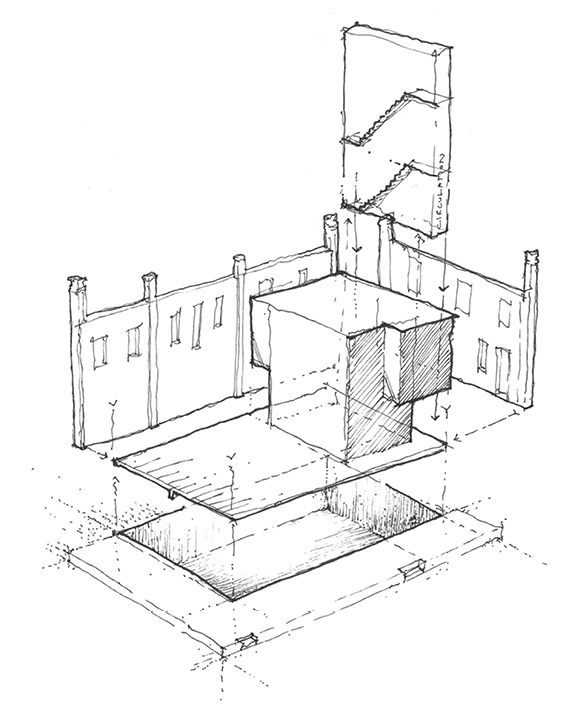

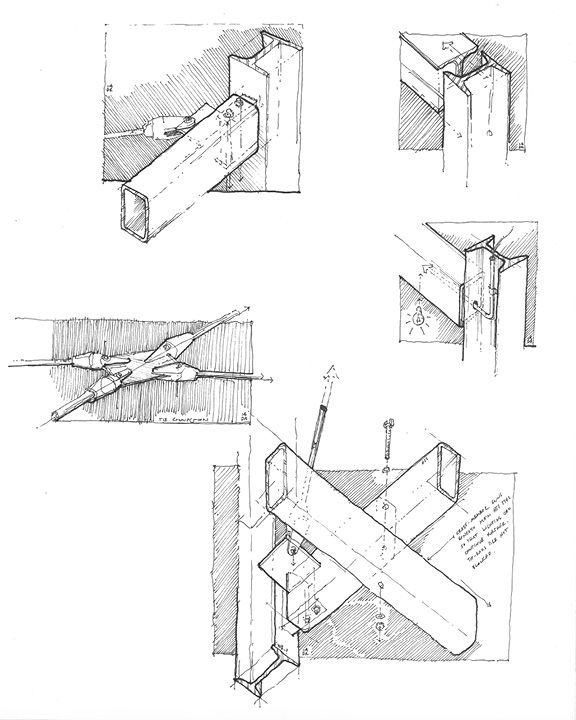

The Volland Store

El Dorado Inc., adaptive reuse of 4,500-square-foot, two-story brick structure, Volland, KS, 2015

- The Volland Store, circa 2000

- Under construction, 1913

- Axon diagram

- Detail sketch, structural frame

- Existing condition, circa 2012

- Floors removed

Common Building Materials

Back to top ↑

Brick, limestone (various types), corrugated metal, wood (charred and uncharred), hedge post, baled prairie hay, heavy timber

This unique style of fence post is believed to have been devised by the African American ranch hands who settled in Dunlap, one of several Exoduster communities in Kansas, in the years after the Civil War. In its composite limestone-and-steel-pipe construction, the Chapman post is believed to be one of few material objects endemic to the Flint Hills. To ensure that the steel pipe didn’t rust from the bottom, fence builders stuffed corn shucks into the pipe and then topped them with concrete. In some counties, fences that employ the post are referred to as “Fulghem fences,” a reference to Harrison Fulghem, a young black ranch hand who lived in the area around this time. Today, the posts are most often referred to as Chapman posts, for Philip Chapman, the Kansas rancher who patented the design in 1903.

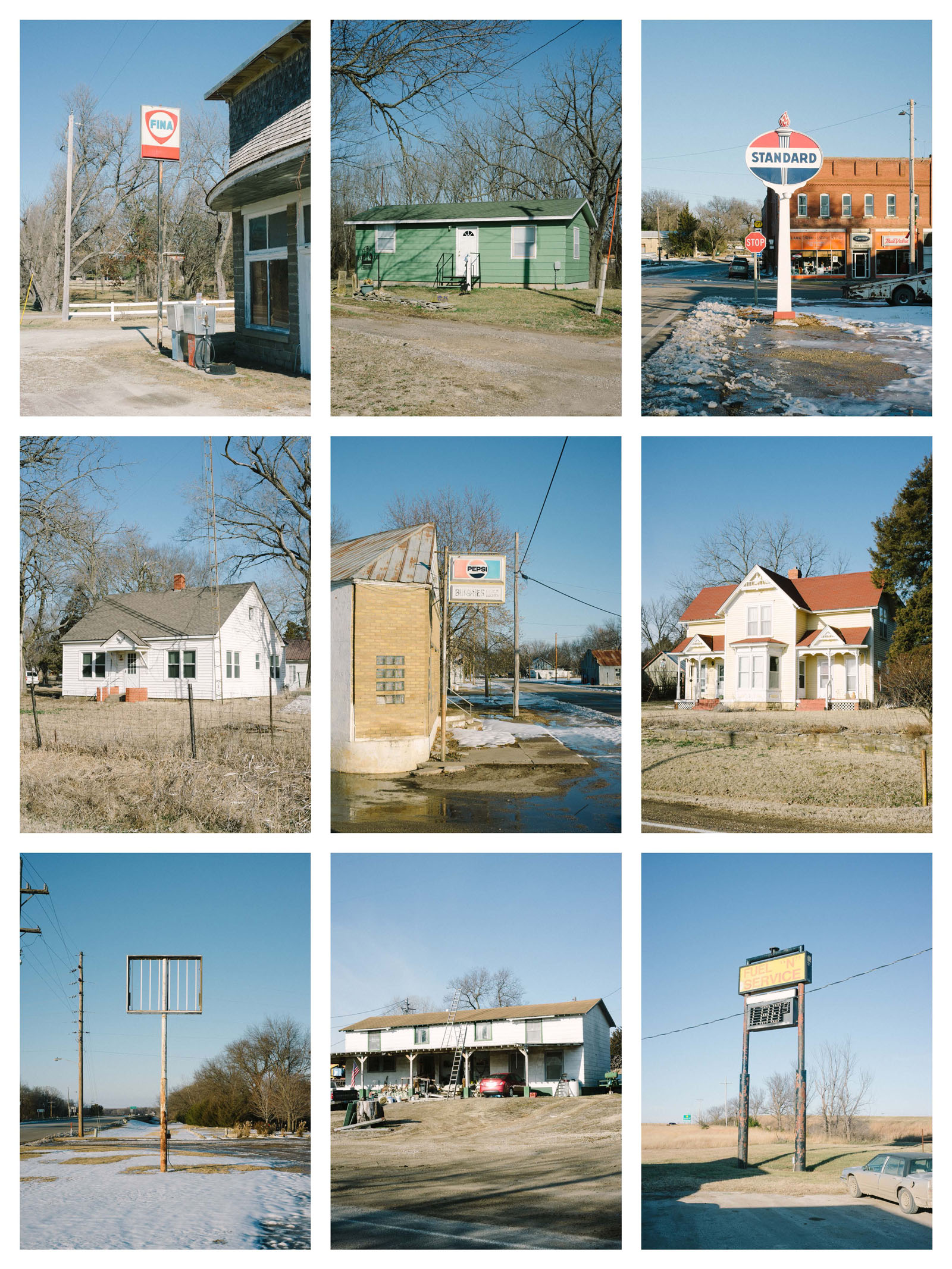

Vernacular Forms

Back to top ↑

Growing up in a rural setting develops an eye for subtle forms — moments when the vast ocean of the prairie is broken by the surface patterns and structures of human development. Driving, riding, and walking on just about every road in the area over the past few years, these vernacular structures have begun to take on a sculptural quality — “skyscrapers” rising up in an isolated horizontal landscape, monuments to the shared priorities and everyday human activity in this place.

Reception & Panel

Back to top ↑Acknowledgements

Back to top ↑This show was made possible with the generous support of Humanities Kansas, the Center for Living Education (now Matfield Green Works), The Volland Store, El Dorado Inc., and Places Journal. Special thanks to Elise Kirk, David Dowell, Hesse McGraw, Luke Koch, Brian Obermeyer, Christy Davis, Jim Hoy, Ben Moore, Rod Harms, Stephanie Rolley, Katie Kingery-Page, Jane Koger, Jesse Solis, Pauline Sharp, Bill McBride, the staff at Camp Wood, Patty Reece, Katherine Hamm, Gary and Mary Schuler, Allison Schuler, and Nancy Levinson.